The racist organization known as the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan mounted a resurgence in the 1920’s following the Hollywood release of D. W. Griffiths classic silent film, “The Birth of a Nation.” The widely popular movie reinforced negative racial stereotypes concerning blacks and portrayed Klan members as heroic. The film’s unparalleled success reflected the prejudices then held by a large portion of the American population.

The Klan first arrived in Detroit in 1921, but the organization quickly spread to Michigan’s northern rural counties. Ku Klux Klan organizers came to Manistique during the early summer of 1923. Four men posing as researchers from the “Sebring Research Bureau” circulated among the population. It soon became known that the group was attempting to organize a branch of the Ku Klux Klan in Manistique.

The local newspapers were silent regarding the Klan’s arrival in Manistique, so it was left to outside news media to report on the Klan’s activities here. However, the Klan’s presence in Manistique was impossible for local residents to miss. Flaming crosses on hilltops illuminated the nighttime sky. A special Michigan edition of the Klan propaganda magazine “The Fiery Cross” was widely distributed throughout the city.

Cloaked in a shroud of patriotism, Klan organizers stressed the importance of loyalty to the constitution and support for law enforcement. Also mentioned, but usually not emphasized, were themes glorifying Protestant

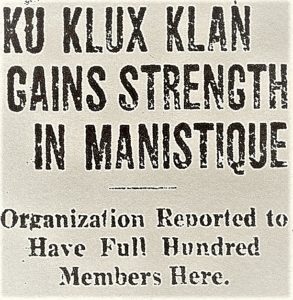

Headline in the August 30, 1923 edition of the “Escanaba Daily Press.”

Christianity and 100 percent Americanism. Klan organizers often recruited community leaders for membership, hoping to build popular support for the movement. The rhetoric designed to entice individuals to join the Klan glossed over a much darker message of racial and religious bigotry targeting Jews, Catholics and African Americans. The Klan’s appeal dovetailed nicely with anti-immigration sentiment which was widespread during the 1920’s, especially against certain “undesirable” eastern and southern European ethnic and religious groups.

Near the end of August, 1923, a public meeting was held in Manistique inviting attendees to join the Klan. The Escanaba Daily Press reported that Klan membership reached 100, including many prominent citizens.

One can imagine the chilling effect the arrival of the Ku Klux Klan may have had on Manistique’s Jewish and Catholic communities. What is known is that prominent Jewish merchants including the Winkelmans, Blumrosens and Rosenthals soon disappeared from Manistique’s business community.

Mercifully, the Klan’s 1920’s resurgence was short-lived. The organization which claimed to be open only to men of “good moral character” was beset by sexual and financial scandals involving its state and national leadership. By 1925, all mention of the KKK in Manistique had disappeared from the headlines.

The damage to the city’s reputation may have been harder to repair. An editorial in the Ironwood Times declared that Manistique’s embrace of the Klan was a “disgrace to the upper peninsula.” What impact the episode may have had on businesses looking to locate in Manistique is unknown.

Just one decade later, the glorification of Aryan supremacy and the scapegoating of religious minorities in Nazi Germany led to the calamity of the Second World War and the holocaust. Those who forget the lessons of the past do so at their peril.