The Alva Kepler Log Cabin, Photo courtesy Lee Ekblad

The Alva Kepler log cabin in Manistique’s Pioneer Park dates back to the 1880’s and was once part of the Byers’ settlement in Hiawatha Township, 12 miles north of Manistique. The cabin became a source of controversy in the mid-1890’s, when Abe Byers and Walter Thomas Mills formed a cooperative community known as the “Hiawatha Village Association.” People who joined the colony promised to move into association housing as soon as it became ready. When Civil War veterans John and Alva Kepler refused to do so, the firestorm it ignited lead to the demise of the Utopian experiment in Schoolcraft County.

The cabin’s story begins with the arrival of Abraham Byers in Manistique in August of 1882. Byers was a farmer from Bangor, Michigan, who was seeking a fresh start and looking for quality land to homestead. While visiting with local residents, Byers heard about some magnificent hardwood forests with clear spring water located 12 miles north of town. Once Byers inspected the area, he knew he had found his future home. He proceeded to the land office in Marquette to put in claims for nine 160-acre parcels: one for himself and eight others for his relatives. These included his sons Lincoln, Elonzo, and Fremont; his son-in-law Ira Lobdell; his brother James Byers and his brothers-in-law John Kepler, Alva Kepler, and Eli Huey. The area became known as the Byers settlement.

The Byers settlement grew and prospered during the 1880s. By the beginning of the 1890s, however, events in other parts of the country began to impact the local economy. It was at this time that Abe was drawn to the populist movement, an outgrowth of the cooperative Farmer’s Alliance of the 1880s. The Populists were concerned about social and economic issues which adversely affected farmers. The People’s Party was organized in Omaha, Nebraska on July 4, 1892 as an alternative to the Democrats and Republicans. The populist platform advocated numerous reforms, including government ownership of transportation; a national currency based on the unlimited coinage of both silver and gold; a graduated income tax; and an eight-hour work day.

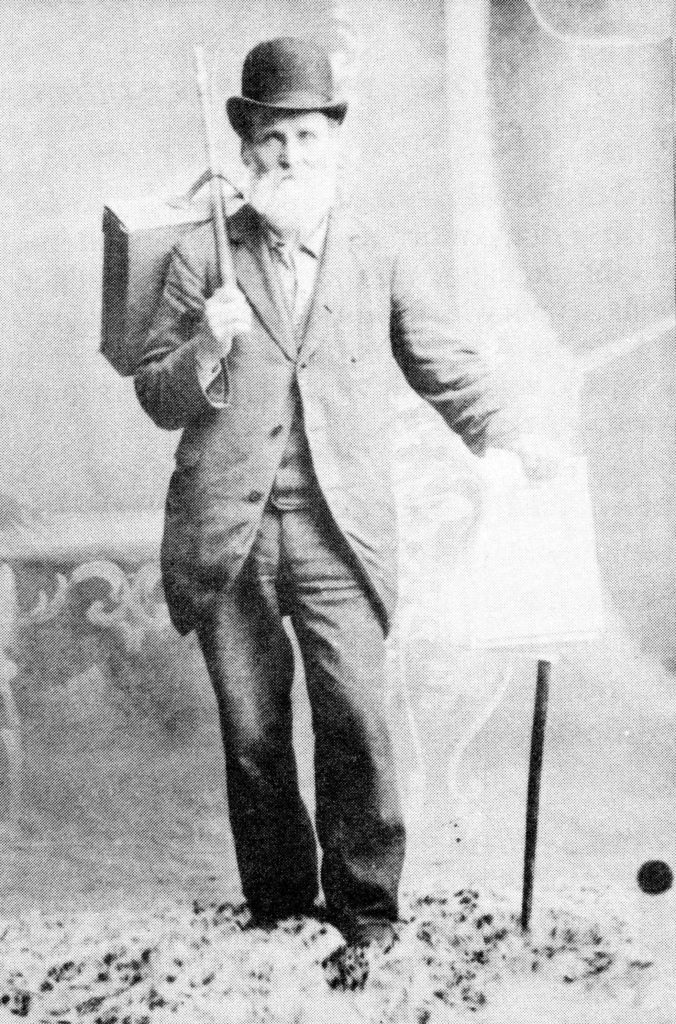

Abraham S. Byers – Photo courtesy Sally Creighton Setterlind collection

Abe Byers became a tireless advocate for the People’s Party cause. He stood on street corners in Manistique, extolling the virtues of the party agenda while he peddled subscriptions to populist magazines and newspapers. Despite his best efforts, the editor of Manistique’s Weekly Tribune speculated that the people were not ready “to turn their affairs over to the tender mercies of the Populists.”

But attitudes began to change following the Panic of 1893, which brought hard times to Schoolcraft County. The crisis started in February of that year with the bankruptcy of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad and the subsequent failure of several banks. As the nation spiraled into a severe economic depression, industrial centers, mill towns, and farmers were the hardest hit. High rates for railroad transportation, currency inflation, and falling prices for agricultural products pinched the pocketbooks of local farmers.

As the depression stretched into 1894, Byers searched for solutions in populist publications. He happened upon a book by famed orator and temperance lecturer, Walter Thomas Mills, titled “The Product Sharing Village.” Mills promoted the establishment of cooperative communities in which the residents would share equally in the fruits of their labor. Byers was so impressed by what he read that he wrote to Mills (who resided in Oak Park, Illinois) and offered to donate his land, along with that of his neighbors, for the creation of a cooperative colony in the U.P. Amazingly, Mills accepted Abe’s proposal, promising to come to Manistique and help with its implementation.

In March 1894, Abe went public with the plan, holding meetings in Manistique and in Hiawatha Township to recruit new families to join the commune.

Spurring residents to consider this cooperative arrangement was the state of the economy in the area; the downturn had severely impacted Manistique’s largest employers, the Chicago Lumbering Company and the Weston Lumber Company. Lumberjack wages in the Upper Peninsula had been slashed from an average of $25 per month in 1893 to only $10 per month the following year.

Walter Thomas Mills – Photo courtesy Wikipedia

Walter Thomas Mills arrived in Manistique a few weeks later. He was an unusually small but distinguished looking man with mutton-chop sideburns. Though short in stature, he was a powerful and eloquent speaker. He delivered a series of lectures at the Star Opera House that were enthusiastically received and swayed local opinion in favor of the enterprise.

In short order, several members of the Byers clan deeded their farms to the colony, legally known as the “Hiawatha Village Association.” These included Abe Byers; his sons Elonzo, Lincoln, Beecher, and William; and Byers’ brothers-in-law, the Keplers, and Eli Huey. Individuals who donated their land agreed to move into association housing as soon as it was ready.

Several newcomers also embraced the cooperative, including many of Mills’ friends and relatives from Iowa. Another social activist from Chicago, John Henry Randall, and his family joined them a year later in the spring of 1895. Randall had recently led an army of marchers to Washington, D.C. to protest the widespread unemployment.

Throughout the summer and fall of 1894, Hiawatha Village was transformed from an idealized concept to a physical reality. At its peak, the colony numbered approximately 225 men, women, and children. Assets included 1,080 acres of land, 125 cattle, and 25 horses.

The ringing of the woodman’s axe and the rhythmic hum of the cross-cut saw were heard throughout the village. Land was cleared for crops, and cabins were constructed for arriving families. The homes were laid out in the shape of a horseshoe with a center courtyard and water well. Use of alcoholic beverages was forbidden on the grounds, and several members voluntarily gave up their tobacco habits as well.

The men of the commune were given a choice among several work assignments including the sawmill, dairy or agricultural departments; shoe shop; or print shop where the association newspaper, The Industrial Christian, was produced. Mills procured a contract from an outside business to produce cant hook poles and peavey shafts for use in lumbering. The colony also had its own blacksmith shop and woodworking establishments.

The women of the colony were also busily engaged in communal work projects. Two women started a laundry, while others labored in soap-making and sewing rooms. Knitted items were manufactured on a machine. Deer hides were tanned and transformed into mittens, shoes, and jackets.

The harvest in the fall of 1894 and 95 yielded bumper crops of potatoes and onions. Regrettably, this produce rotted in the cellars for lack of a local market and exorbitant rates for transportation. The Chicago Lumbering Company, which employed hundreds of hungry lumberjacks in the numerous camps scattered throughout Schoolcraft County, refused to purchase the colony products at any price. They also held a near monopoly on shipping by water and charged more for transportation than the produce would sell for in Milwaukee or Chicago.

By the spring of 1895, dissension began to set in. The colonists, including many newcomers from Iowa, had just emerged from a long, cold Upper Peninsula winter. There also must have been lingering disappointment regarding the failure to find a ready market for the previous year’s potato harvest. Seeds of controversy were sown by “outsiders.” Many of the villager’s neighbors were suspicious of Walter Thomas Mills and they started rumors that the cooperative community was just a scheme by Mills to enrich himself and gain control of the colonists’ property.

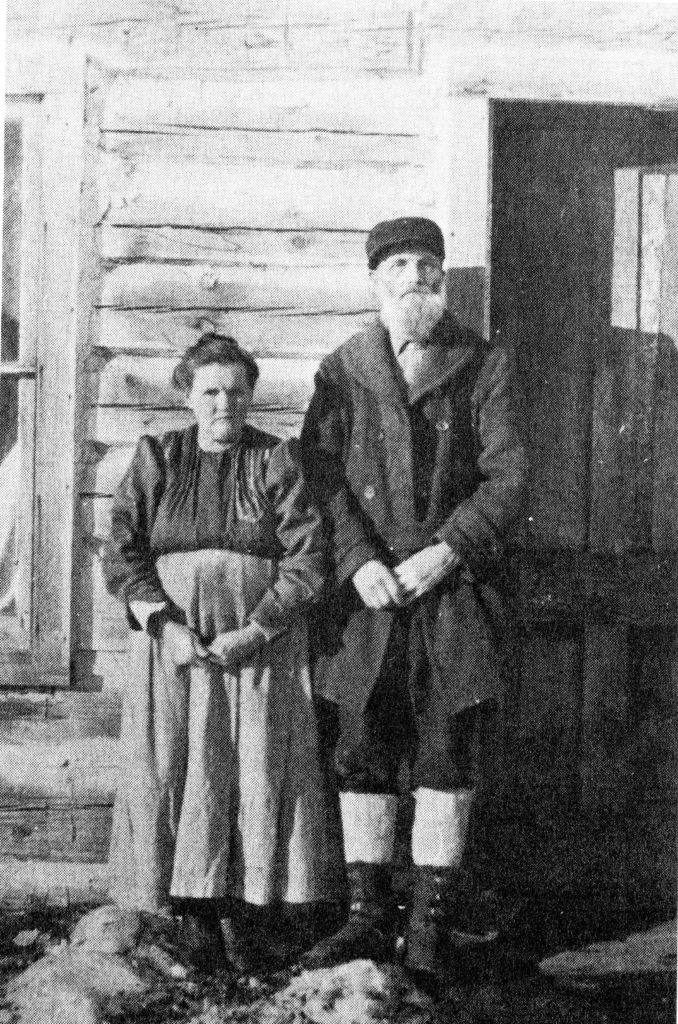

John and Elvila Kepler, Annis Repp Carney Photo

The first sign of discord occurred when two association members, John and Alva Kepler, declined to move into association housing. The Keplers were Civil War veterans who steadfastly refused to give up their homes despite Abe Byers’ efforts to convince them otherwise. In the midst of the crisis, Mills consulted a lawyer in Chicago who advised him that the association could force the Keplers to move. When Mills and members of the commune showed up at the home of John Kepler, he greeted them at the door with a shotgun. Other members slipped in though the rear entrance and started moving out the furniture. Kepler’s wife, Elvila, rushed forward to protest. In the melee that followed, Elvila was shoved aside by Mills and “handled pretty roughly.” The Keplers’ belongings were taken away and their cabin dismantled. The same fate befell Kepler’s brother Alva.

A tearful Kepler went to the home of fellow veteran Francis Dodge for advice. Dodge was a highly respected citizen of Hiawatha Township who had decided not to join the association. Dodge drove Kepler 10 miles “over sand ruts and corduroy roads” to the county seat in Manistique, where they met with the prosecuting attorney. Arrest warrants were then issued for Walter Thomas Mills and four other association members. All were charged with assault and battery.

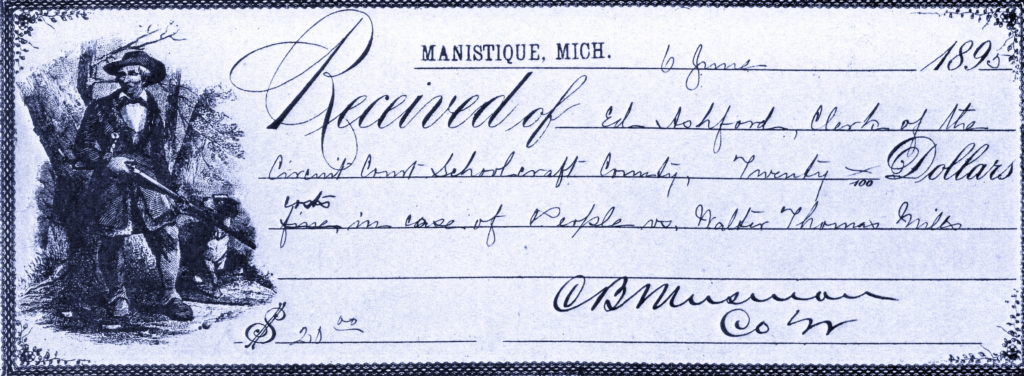

Mills’ trial was held on May 3, 1895 in Manistique. He was required to pay a $50 fine and $20 in court costs or serve 90 days in jail. Mills appealed this sentence and his fine was eventually reduced. Kepler also filed suit to have his farm property returned to him. In an attempt to mend the rift, the entire colony turned out to rebuild the log cabins of both John and Alva Kepler.

Receipt for fine paid by Walter Thomas Mills, June 6, 1895 – Schoolcraft Co. Circuit Court Archives

However, with the Kepler precedent set, more members brought suit against the association, and each time association property was restored to the original owner and costs were assessed. Other members chose not to bring suit, but left to pursue more lucrative employment opportunities elsewhere. In the fall of 1895, with the prospect of enduring another Upper Peninsula winter, and a cash crop of onions rotting in the cellars for lack of a market, Mills and his friends and relatives from Iowa also abandoned the colony. When Mills resigned as President of the association, Abe’s son David assumed the position and was left with the task of sorting out the association’s affairs.

Each member who decided to pull out was provided with assets that would be nearly equal to the personal property, cash or stock that they had initially invested. David reported that there were few arguments and no “hard feelings.” Mills, his parents, brothers and sisters lost everything that they had put into the colony, but the association sold some of the stock “to help them get away.”

In little more than a year’s time, the experiment in Upper Peninsula communal living effectively drew to a close.

Mills blamed the failure of the colony on the opposition of the Chicago Lumbering Company, which he referred to as “a great business corporation owned by non-residents and controlled by absent owners.” The lumber company held a monopoly on almost every item the colony’s residents needed to purchase to supply the colony store and when it came time to sell a cash crop of nine thousand bushels of potatoes “as fine as were ever grown,” the lumber company was the only buyer—and they refused “at any price.” The lumber company also controlled the shipping and set the freight rates higher than the market value of the products.

Abe’s son David Byers discounted the lumber company as the cause of the association’s failure. Instead, he cited poor business practices along with an even more basic reason for the failure of the colony: the nature of man. As he explained, “They want constant struggle to get ahead of the other fellow” and they “won’t do their best if they think the other fellow is going to share some of the harvest.”