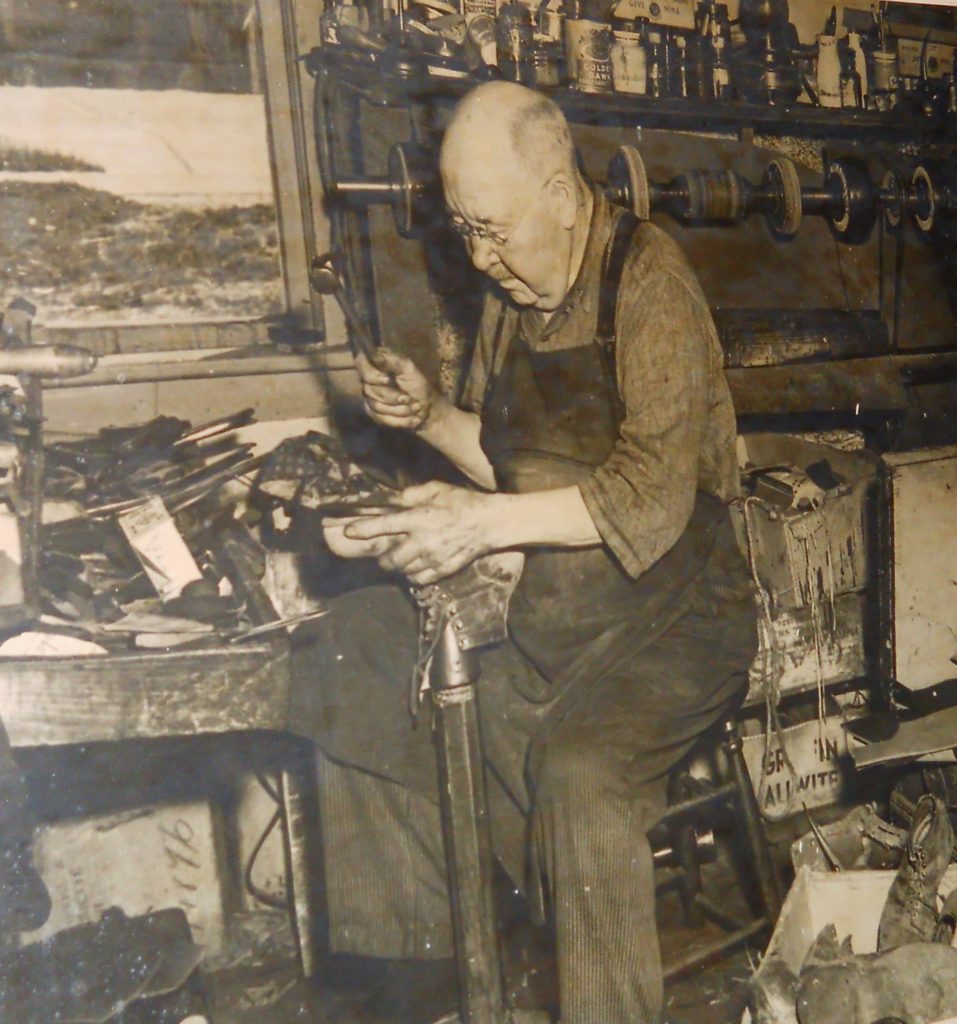

Ekberg is pictured here in his shoe shop in 1948

Charles Ekberg was born in Skåne County in southern Sweden on April 30, 1862. His early childhood was marked by hunger and deprivation. Charles was still an infant when his father was killed in a tragic accident that catapulted his family into poverty. Nine years later, his mother followed her husband to the grave. Heartbroken after his mother’s death, Ekberg despaired for his future. The authorities planned to provide for the boy by sending him to reside with a humorless neighbor couple, where he would work for his room and board.

When the day came for young Ekberg to be turned over to the custody of strangers, he vowed to run away. He was to begin his new life with the neighbor couple on Sweden’s most celebrated holiday, Saint John’s Day, which took place in midsummer. The festival presented the perfect opportunity for a small boy to disappear into the crowds. Left on his own for a time, Charles made his way to the depot. Unnoticed by the attendant at the station, Ekberg boarded an excursion train bound for Lund where he spent the day. When the celebration was concluded, the boy managed to sneak aboard a second train; this one headed for the seaport city of Malmö. While at the dock, he squeezed in among a crowd of travelers, boarding a ship bound for Copenhagen, Denmark.

Tired and hungry, Ekberg wandered aimlessly for hours through the streets of Copenhagen, arriving finally in front of a market filled with fruits and vegetables. The shop owner noticed the boy staring yearningly at his produce, and he asked the boy if he wanted a job. The grocer fed the child and put him to work sorting potatoes and picking off the sprouts. A bed was provided in the attic of the grocer’s home. Before long, Ekberg earned enough money to buy his first pair of leather shoes and some new clothes.

Charles worked hard and had an outgoing personality. The grocer looked after him until he found him a steady job as a cabin boy on a steam boat sailing between Copenhagen, Denmark and Hull, England. The ship’s captain took young Ekberg under his wing, and taught him to read and write. He also schooled him in proper manners.

After Charles had worked four years as a cabin boy, the captain arranged for the lad to be apprenticed as an iron worker on condition that he complete his neglected religious education by learning the Lutheran Catechism and being confirmed. Ekberg fulfilled his promise to the captain and was confirmed, but an accident at the foundry left his vision so impaired that he was forced to learn a new trade. By the time Ekberg reached the age of 17 he had completed an apprenticeship with a shoemaker and was dreaming about what life could be like in America!

The passage to America cost him nearly all of his savings from his work as a journeyman shoemaker. He arrived in New York during the spring of 1880 with $1.80 in his pocket. Job recruiters came daily to the port of entry, and Ekberg soon found himself riding in a boxcar with a group of other immigrants bound for Tonawanda, New York.

Tonawanda, New York was located on the shore of Lake Erie, where three-masted schooners unloaded their cargos of pine and hardwood lumber from the forests of the Great Lakes region. Upon his arrival at the Weston Lumber Company in Tonawanda, Ekberg was assigned to work with a soft spoken, unassuming gentleman who liked to whittle. With a wagon and team of horses, the two men went about setting up the framework for lumber piles. Each set of timbers would be carefully leveled off and secured before moving on to the next. As the days wore on Ekberg would often see the man he had worked with on that first day. He would sit quietly at the dock turning a stick of wood into shavings, while other workers scurried all around him.

One day while unloading a schooner from a lumber mill in Michigan, Ekberg heard about the town of Manistique, where there was a large Scandinavian community and plenty of jobs in the mills. Ekberg determined that he would go there. He arrived in Manistique on June 29, 1880 and was assigned a job as a common laborer in the lumber yard. One day while working in the harbor, he spied his friend the whittler disembarking a schooner from Tonawanda. It was only then that Ekberg discovered who his soft spoken friend actually was: Abijah Weston, owner of the Chicago Lumbering Company.

Ekberg stayed in Manistique for only a short time before his urge to wander became too much for him to resist. He made his way first to Escanaba where he worked at the ore docks using “pike poles” to shove iron ore into the holds of ships. Describing the foreman, who yelled and cursed constantly, as a “slave driver,” he moved on to Menominee—and eventually made his way to Chicago. He was employed there as a bricklayer’s helper prior to finding a job more in line with his training in a shoe store. All the while he was in Chicago, his thoughts took him back to Manistique where he longed to return.

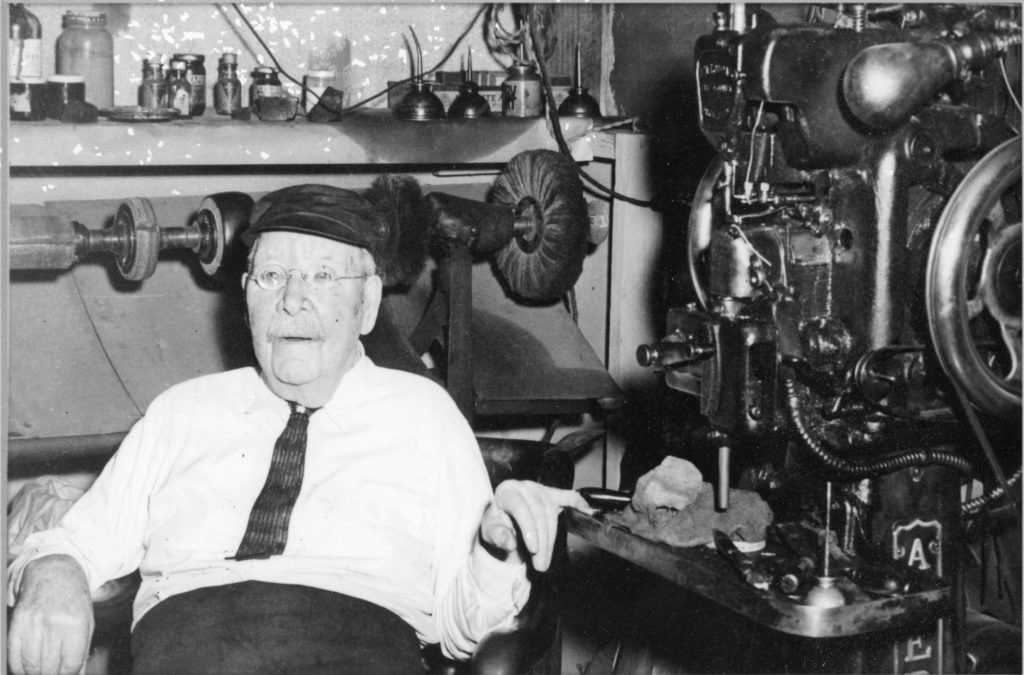

Charles Ekberg in 1955 on the occasion of his 94th birthday. Vern Linderoth photo courtesy the Fish Family

After he had saved $110 from his job in the shoe store, he purchased a supply of leather, a stitching machine, shoemaker’s tools and passage on a boat to Fayette, Michigan. When he arrived at Fayette, he arranged for his supply of leather and tools to be placed on the stage to Manistique the following day. Not having enough money to purchase a ticket for himself, he hiked across country to Manistique, slogging through the wet snow of early spring.

Ekberg met with the superintendent of the lumber mill, Martin Henderson Quick, and secured credit to purchase the lumber required to erect a store building. The lumber company bosses owned all of the property in Manistique, and they assigned him a spot on Chippewa Avenue where he could build and open his business. Ekberg made and repaired shoes in Manistique for over 60 years, working well into his 90’s. In the early days the majority of his business consisted of work shoes for lumber jacks and mill hands. But he also made dress shoes for both men and women. When interviewed by a reporter for his 94th birthday in 1955, Ekberg showed off a pair of ladies shoes he had made 60 years earlier. They were very sharply pointed at the toe and 14 inches tall.

Charles Ekberg (center) pictured here with his four children in 1932.

Ekberg maintained a relationship with Abijah Weston for several years after he opened his store. Weston would stop into his shoe shop and visit—sometimes for hours. After he left, Ekberg would sweep up nearly a bushel of shavings off the floor, as Weston whittled all the while he talked.

Charles Ekberg married Hanna Peterson in Manistique on February 25, 1885. The couple had four children, Ruth, Hulda, Fred and Emil. Hanna died first in November of 1924 at age 59. Her husband survived her by more than three decades. Ekberg’s cobbler shop tools and equipment were donated to the Schoolcraft County Historical Society by the Fish family and are on permanent display.

Research for this post included an article by James Lowell on the occasion of Ekberg’s 94th birthday.