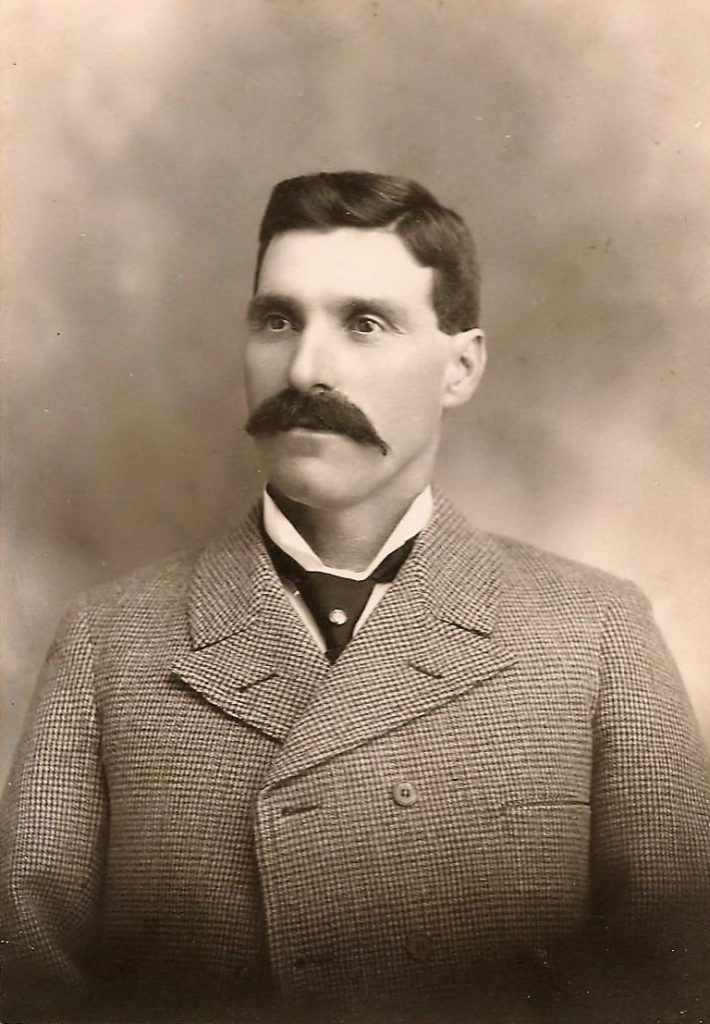

1880’s image of Edwin Cookson. Photo courtesy of Anthony Perkins

Edwin Cookson was born in Greenfield, Maine, in May of 1854. He was the second oldest child in a family of six boys and 2 girls. His parents, Joseph and Maria Cookson owned a farm in Greenfield, but all of their sons worked as loggers and river drivers in Maine.

During the early 1870’s Edwin Cookson migrated west to Oshkosh, Wisconsin. There in 1878 he responded to a “Help Wanted” ad posted in the Oshkosh papers. Ebenezer James was seeking laborers to work at the James Brothers sawmill east of Manistique.

Cookson was employed as a teamster with the James Brother’s mill and also homesteaded property in Manistique Township. The Jamestown mill was in operation from 1875 to the early 1880s, but went out of business due to the difficulty in keeping the mill supplied with logs. The majority of the company’s timber holdings were in the area of Thunder Lake and Murphy Creek. The logs had to first be rafted across Indian Lake, then floated down the Indian River, and finally they were towed upstream on the Manistique River to the Jamestown mill. But the Manistique River was also used by the Chicago Lumbering Company to transport their timber, which made it nearly impossible for the Jamestown men to keep their mill supplied with the raw material to produce finished lumber.

Above is a circa 1870’s photo of the Jamestown sawmill which was located just east of town on the Manistique River. The mill was in operation from 1875 to about 1882. SCHS photo.

During the winter of 1879, Edwin Cookson was working at the Ebenezer James camp on Stutt’s Creek. The camp food that winter was plentiful but the quality was poor. The cooks served redhorse, sowbelly (mess pork), black molasses (blackstrap), dried apples, prunes and cooked applesauce. Staples such as sugar, butter and coffee were nowhere to be found.

After the Jamestown mill closed, Cookson worked for the Chicago Lumbering Company as a teamster, and in the evening he was the camp blacksmith. He held this position for several years before being made a camp foreman. He later served 14 years as “Walking Boss” in charge of all the company’s woods operations.

An early Schoolcraft County Logging Photo. Edwin Cookson worked as a teamster for both the Jamestown Company and the Chicago Lumbering Company

Nearly every phase of lumbering was fraught with danger, but one of Cookson’s closest calls came in the autumn of 1882 while asleep at the Tucker lumber camp north of Manistique. Two trees came crashing down across his tent. The first tree came to rest on a stump and the second tree fell on top of the first. Cookson was left with a space of about 12 inches to rest unharmed—but maybe a little claustrophobic.

While Cookson was working as a walking boss for the Chicago Lumbering Company, George Orr asked him if he would agree to be a foreman at a lumber camp north of Seney. The lumber company was having a hard time keeping foremen at the Seney camp due to men bringing liquor into camp. Edwin Cookson did not drink alcohol and was firmly resolved not to allow it in camp. He informed every man he hired that his lumber camp would be “dry” and that he would not allow alcohol to be kept or drank in camp. Any man caught violating this order would be fired.

Cookson’s Seney camp ran smoothly until near the holidays, when one of his teamsters brought in a jug of whiskey. Cookson soon noticed two of his men under the influence, and resolved to find the offending jug of whiskey. He searched the stables, and the oat bins, and finally located the jug in a feed box under a manger in one of the horse stalls. After locating the jug, he took it outside and smashed it to pieces, spilling the contents out on the ground. Cookson was a large man who could stand up for himself, and who earned the respect of the men working under him. During his two years as foreman at the Seney camp, Cookson only had to dismiss four lumberjacks for drinking or bringing liquor into camp.

Edwin Cookson was called home to Maine in 1888 due to the death of his mother. When he returned he brought his younger brother Frank with him. Edwin Cookson was a lumber camp foreman with the Chicago Lumbering Company at the time and Frank worked for him. He soon rose to positions of responsibility including lumber camp forman and was also placed in charge of river drives on the east branch of the Fox River. When the brothers returned to Maine for a visit in 1897 they brought back their nephew, Harvey Saunders, who soon was put in charge of river drives on the Driggs River. All three men became legendary in the early lumbering history of Schoolcraft County. After leaving the Chicago Lumbering Company, Cookson purchased some timberland and worked for many years as a lumber jobber.

Cookson lived a long life and shared many stories about the early days of logging in Schoolcraft County. He passed away in December of 1936 at the age of 82. He was survived by his sons Clarence and Lawrence of Milwaukee. He was also survived by a sister, Mrs. Elsie Madden of Milford, Maine. His brother, Frank Cookson, preceded him in death in January of 1932.