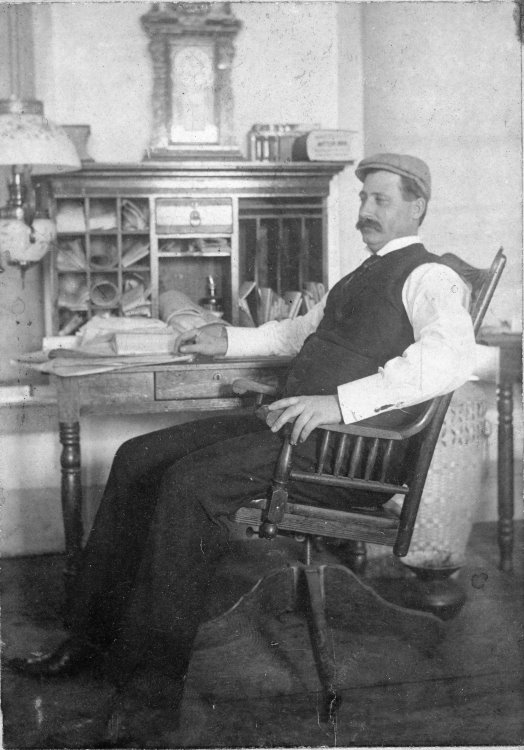

George Holbein at his desk in the newspaper office.

George Holbein was born on August 16, 1864 at Dennison Station, Summit County, Ohio. He was the fourth child in a sibling group of eight born to Elias and Lydia Holbein. Only four of George’s siblings survived to adulthood.

George’s father, Elias Holbein was a skilled leather worker who crafted saddles and harnesses for horses. Elias was an educated man who was active in his German Reformed Church congregation, where he served as deacon, secretary and Sunday school superintendent. He was praised as having “an even temperament and a genial spirit.”

When George was 8 years old, his father had saved enough money to purchase a farm in Summit County, Ohio. The family was settled into their new home for only about a week when Elias came down with a cold which quickly developed into pneumonia. He died a few days later on March 30, 1873 at age 42. Elias left his widow Lydia and five minor children including: Romina, age 16; George, 8; Charles, 7; Joseph, 5 and an infant son William; without any means of support. Lydia and her children soon left their new home and moved in with Lydia’s widowed father, Joseph Kulp, who owned a farm in Wadsworth Village, Medina County, Ohio.

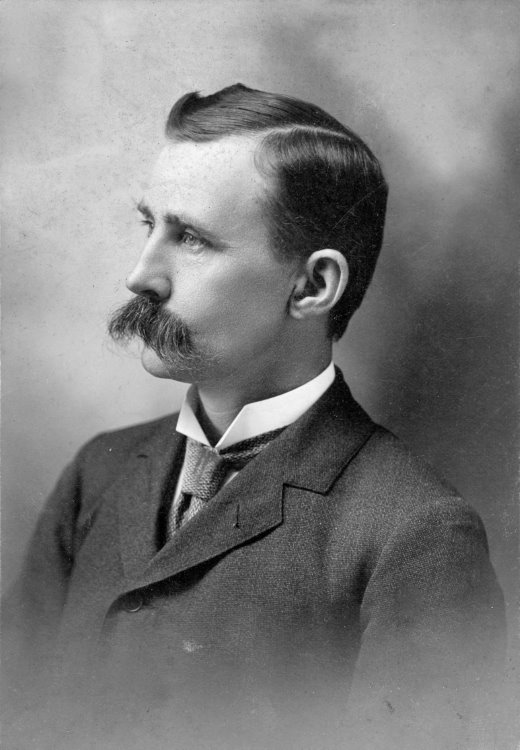

George Holbein circa 1890s. SCHS Photo

George grew up on the farm in Wadsworth Village and attended the local schools. When not in school he and his brother Charles worked on his grandfather’s farm. After graduation, George attended Heidelberg University in Tiffin, Ohio. The university was associated with the German Reformed Church (known today as the United Church of Christ) and provided a theological education. The goal of the university was to train Christian scholars.

In 1883 at age 19, Holbein took up an apprenticeship as a printer in Hiawatha, Kansas and later became editor of the Hiawatha Democrat newspaper. By 1888 he had moved on to Atchison, Kansas, where he became the editor of the Atchison Patriot.

On October 29, 1890, Holbein married Mary Riedinger, a school teacher from Randolph, Ohio in Portage County. Within a year the couple had relocated to Manistique, Michigan where they lived out the remainder of their lives.

In 1892, Holbein purchased the Saturday Morning Star which he dissolved. Shortly thereafter he began publication of his new newspaper, the Weekly Tribune, which competed with Wright E. Clarke’s Pioneer and Thomas MacMurray’s Manistique News and later with James MacNaughton’s Courier and Benjamin Gero’s Record.

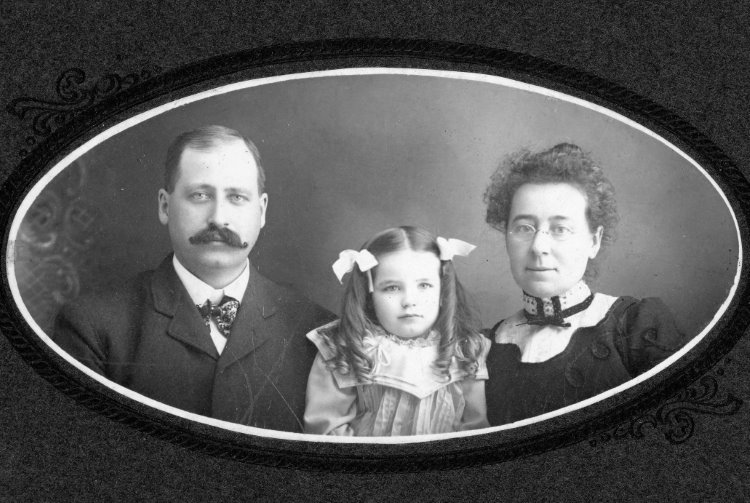

George & Mary Holbein with their daughter Grace circa 1903. SCHS Photo.

More than equal to the task, his competitors in business soon began referring to him as “old beanhole,” a term of grudging respect. Holbein immediately distinguished his newspaper with its fine coverage of Manistique’s great fire in September of 1893. Upon the death of Wright Clarke in May of 1896, Holbein purchased the Pioneer and merged the two papers, forming the Manistique Pioneer-Tribune. Holbein became a worthy successor to Clarke in advocating for improvements in the community and promoting its welfare and advancement. Holbien’s tenure at the Tribune Publishing Company spanned the years between 1893 and 1917 which coincided with the decline in big pine lumbering and the heyday of Manistique’s industrial era.

In a tribute to a fellow editor, James MacNaughton, upon his death in 1910, Holbein observed . . .”he, as can be said of every newspaper man who cast his lot in a city the size of Manistique, was not appreciated to the extent that he should have been, by the community for whose advancement he gave the best years of his life, and life itself. . . . Ingratitude kills more newspaper men than hard work.”

In 1898, after eight years of marriage the Holbein’s remained childless. The couple made the decision to adopt—and into their home came a newborn baby girl, whom they named Grace. She became the light of their lives.

Grace Holbein circa 1906. SCHS file

Mary and George Holbein circa 1916.

The newspaper business was not Holbein’s only interest. He was active in politics and worked tirelessly to support Republican candidates. He was rewarded with an appointment by Governor Charles Osborn as oil inspector for five eastern upper peninsula counties. Like his father before him, Holbein was also active in his church, regularly attending Presbyterian services in Manistique. There were excursions to Indian Lake camping in tents, which were in general use before cabins were built. Longer vacations were spent traveling by train to Ohio, where they visited friends and relatives.

During the last seven years of his life Holbein’s health began to fail. In 1910, he became violently ill at work and nearly died from a bleeding ulcer. Progressive heart disease sapped his strength and energy. He spent the final year of his life editing his paper from his home as he was too weak to go into the office. He sold the paper in December of 1916, a few months prior to the United States entry into World War I. George Holbein passed away on May 12, 1917 at age 53, long before what should have been his “allotted span of years.” Among Upper Peninsula editors, he was considered a giant of his era—celebrated both for the forthrightness of his character and his talent with his pen.