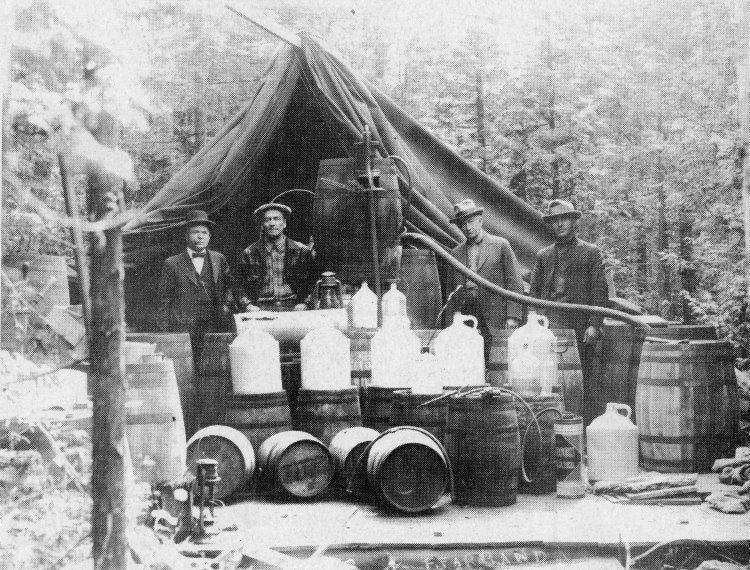

Sheriff Jack Hewitt (left) and Deputy Matt Kasun (rt.) with confiscated still. Photo courtesy the Lundstrom Collection.

The die was cast on November 8, 1916. Michigan voters went to the polls and overwhelmingly approved an amendment to the Michigan State Constitution prohibiting the manufacture, sale and transportation of alcoholic beverages. In an era prior to women’s suffrage, the statewide tally was 353,378 dry to 284,752 wet. The state prohibition amendment became the law in Michigan eighteen months later on May 1, 1918.

The immediate impact of state prohibition was to put local saloons, along with hotel bars and restaurants out of the liquor business. Those businesses that didn’t close their doors were converted to soft drink parlors, billiard rooms or lunch counters. These new establishments became popular places for social gatherings, but also fell under increasing scrutiny by law enforcement officials. The ratification the 18th amendment to the U.S. Constitution in January of 1919 ushered in national prohibition one year later on January 17, 1920.

The election of John Hewitt as Schoolcraft County Sheriff in 1926 signaled hard times ahead for dry law violators. Tough as nails, Hewitt was an old school lawman who became legendary for his zealous enforcement of prohibition. The sheriff conducted numerous raids all over Schoolcraft County arresting moonshiners, while confiscating illegal stills and barrels of white lightening.

In July of 1928, a Hiawatha township citizen appeared in court on a game law charge of illegal possession of venison. While the court hearing was in session, Sheriff Hewitt paid a visit to the poacher’s place; a remote shack a few miles from the main Hiawatha road and assessable only by way of a secluded forest trail. A search of the shack and surrounding property uncovered a double still, finished moonshine, two stoves, boilers, coolers, mash and rye. The culprit was subsequently arrested and confessed to ownership of the still. A record of two prior convictions for violation of prohibition laws resulted in a sentence of one to two years in Jackson prison.

On another occasion, Sheriff Hewitt employed stealth and patience to nab two moonshiners in Thompson township. The moon distillery operation was located in swampy ground a half mile from the nearest road. Sheriff Hewitt and deputy Matt Kasun crept through the thick undergrowth—slogging through a muddy quagmire to catch their prey. Upon arrival at the site of the still, the officers hid in the brush and waited patiently for the bootleggers (who were camping nearby) to present themselves. Seized in the raid were a 50-gallon boiler, a four-burner oil stove, coils, numerous jars of finished stump juice ready for market and fourteen 15-gallon capacity kegs filled with moonshine. The total market value of the confiscated goods was nearly $3,000.

Confiscated liquor from somewhere in Schoolcraft County. Pictured from left: unknown, Sheriff Jack Hewitt, Pros. Attorney Virgil Hixson, and Deputy Matt Kasun. Photo courtesy the Lundstrom Collection.

In March of 1927, a party by high school students led to the largest haul of moonshine by lawmen in Manistique up to that time. Without the knowledge of his parents, the son of the alleged moonshiner sold pint bottles of hooch to his adolescent friends for 50 cents per bottle. Reports of tipsy teens alerted law enforcement officers to the presence of locally manufactured white lightening. Further investigation by the police resulted in the issuance of a search warrant for a home on North Mackinac Avenue. The surprise raid was conducted by Sheriff Jack Hewitt, Undersheriff L. B. Chittenden, and Chief of Police John Peterson. Confiscated in the raid were a 50 gallon still complete with filtering apparatus; 35 gallons of moonshine ready for sale and 6 barrels of corn mash. The still had been crafted with great care and produced a high-quality home brew. It took officers an hour and a half to load all of the moonshine and liquor making paraphernalia into a truck for transportation to the county jail pending trial.

Attitudes began to change regarding the wisdom of prohibition laws following the stock market crash in October of 1929 which marked the beginning of the great depression. As markets continued to slide downward and the number of unemployed Americans mushroomed, politicians began to view alcohol differently. A restored liquor industry would provide jobs for thousands of Americans. Taxes on liquor and license fees for establishments that served alcohol were another untapped source of revenue for financially strapped state and local governments. Conversely, efforts to enforce dry laws cost federal and state governments millions of dollars annually.

The excesses of the prohibition era were most clearly demonstrated in January of 1929 when Manistique resident Tony Papich was sentenced to a mandatory life term in prison as a habitual criminal after a fifth felony conviction; all for violation of the dry law. His sentence (along with that of four other Michigan residents similarly convicted) was later commuted by Michigan’s governor.

On November 8, 1932, voters in Michigan overwhelmingly approved the repeal of state prohibition. The vote in Schoolcraft County mirrored the state results, with “wets” winning the day by a super majority of 1,350 to 182. Five months later, on April 10, 1933, Michigan became the first state to ratify the 21st amendment repealing national prohibition. The era came to an end on December 5, 1933 when Utah became the 36th state to vote for approval of the amendment.

To learn about the historical society’s new museum fund drive, see the “About Us” tab at the top of the page.